Electrify your NodeJS AWS Lambdas with Rust

Introduction<<

NodeJS runtime for AWS Lambda is one of the most used and for good reasons. It is fast with a short cold start duration, it is easy to develop for it, and it can be used for Lambda@Edge functions. Besides these, JavaScript is one of the most popular languages. Ultimately, it “just makes sense” to use JavaScript for Lambdas. Sometimes, we might find ourselves in a niche situation where would want to be able to squeeze out a little bit more performance from our Lambda. In these cases, we could rewrite our whole function using something like Rust, or we could rewrite only a portion of our code using Rust and call it from a NodeJS host using a mechanism named foreign function interface (FFI).

NodeJS provides an API for addons, dynamically-linked shared objects written usually in C++. As we might guess from the title, we are not required to use C++. There are several implementations of this API in other languages, such as Rust. Probably the most knowns are node-ffi or Neon.

In this article, we would use Neon to build and load dynamic libraries in a NodeJS project.

Build a Dynamic Library with Neon<<

To make a function call to a binary addon from NodeJS, we have to do the following:

- Import the binary addon into our JavaScript code. Binary modules should implement the Node-API (N-API) and usually, they have to

.nodeextension. Using therequirefunction from CommonJS, we can import them. In the case of Neon, this N-API implementation is hidden from us, we don’t have to worry much about it (as long as we don’t have to do some advanced debugging) - In the implementation of the binary code we have to apply some transformation of the input data. The types used by JavaScript may not be compatible with the types used by Rust. This conversion has to be done for the input arguments and the returned types as well. Neon provides the Rust variant of all the primitive JavaScript types and object types.

- Implement our business logic in the native code.

- Build the dynamic library. Rust makes this step convenient by being able to configure the

[lib]section in the project’stomlfile. Moreover, if we are using Neon to initiate our project, this will be configured for us out of the box.

As for the first step, we would want to create a Rust project with Neon dependency for building a dynamic library. This can be done using npm init neon my-rust-lib. To be more accurate, this will create a so-called Neon project, which means it already has a package.json for handling Node-related things. The project structure will look something like this:

my-rust-lib/

├── Cargo.toml

├── README.md

├── package.json

└── src

└── lib.rs

If we take a look at the package.json, we will find something that resembles the following:

{

"name": "my-rust-library",

"version": "0.1.0",

"description": "My Rust library",

"main": "index.node",

"scripts": {

"build": "cargo-cp-artifact -nc index.node -- cargo build --message-format=json-render-diagnostics",

"build-debug": "npm run build --",

"build-release": "npm run build -- --release",

"install": "npm run build-release",

"test": "cargo test"

},

"author": "Ervin Szilagyi",

"license": "ISC",

"devDependencies": {

"cargo-cp-artifact": "^0.1"

}

}

Running npm install command, our dynamic library will be built in release mode. Is important to know that this will target our current CPU architecture and operating system. If we want to build this package for being used by an AWS Lambda, we will have to do a cross-target build to Linux x86-64 or arm64.

Taking a look at lib.rs file, we can see the entry point of our library exposing a function named hello. The return type of this function is a string. It is also important to notice the conversion from a Rust’s str point to a JsString type. This type does the bridging for strings between JavaScript and Rust.

use neon::prelude::*;

fn hello(mut cx: FunctionContext) -> JsResult<JsString> {

Ok(cx.string("hello node"))

}

#[neon::main]

fn main(mut cx: ModuleContext) -> NeonResult<()> {

cx.export_function("hello", hello)?;

Ok(())

}

After we built our library, we can install it in another NodeJS project by running:

npm install <path>

The <path> should point to the location of our Neon project.

Building a Lambda Function with an Embedded Dynamic Library<<

In my previous article Running Serverless Lambdas with Rust on AWS we used an unbounded spigot algorithm for computing the first N digits of PI using Rust programming language. In the following lines, we will extract this algorithm into its own dynamic library and we will call it from a Lambda function written in JavaScript. This algorithm is good to measure a performance increase in case we jump from a JavaScript implementation to a Rust implementation.

First what we have to do is generate a Neon project. After that, we can extract the function which computes the first N digits of PI and wrap it into another function providing the glue-code between Rust and JavaScript interaction.

The whole implementation would look similar to this:

use neon::prelude::*;

use num_bigint::{BigInt, ToBigInt};

use num_traits::cast::ToPrimitive;

use once_cell::sync::OnceCell;

use tokio::runtime::Runtime;

#[neon::main]

fn main(mut cx: ModuleContext) -> NeonResult<()> {

cx.export_function("generate", generate)?;

Ok(())

}

// Create a singleton runtime used for async function calls

fn runtime<'a, C: Context<'a>>(cx: &mut C) -> NeonResult<&'static Runtime> {

static RUNTIME: OnceCell<Runtime> = OnceCell::new();

RUNTIME.get_or_try_init(|| Runtime::new().or_else(|err| cx.throw_error(err.to_string())))

}

fn generate(mut cx: FunctionContext) -> JsResult<JsPromise> {

// Transform the JavaScript types into Rust types

let js_limit = cx.argument::<JsNumber>(0)?;

let limit = js_limit.value(&mut cx);

// Instantiate the runtime

let rt = runtime(&mut cx)?;

// Create a JavaScript promise used for return. Since our function can take a longer period

// to execute, it would be wise to not block the main thread of the JS host

let (deferred, promise) = cx.promise();

let channel = cx.channel();

// Spawn a new task and attempt to compute the first N digits of PI

rt.spawn_blocking(move || {

let digits = generate_pi(limit.to_i64().unwrap());

deferred.settle_with(&channel, move |mut cx| {

let res: Handle<JsArray> = JsArray::new(&mut cx, digits.len() as u32);

// Place the first N digits into a JavaScript array and hand it back to the caller

for (i, &digit) in digits.iter().enumerate() {

let val = cx.number(f64::from(digit));

res.set(&mut cx, i as u32, val);

}

Ok(res)

});

});

Ok(promise)

}

fn generate_pi(limit: i64) -> Vec<i32> {

let mut q = 1.to_bigint().unwrap();

let mut r = 180.to_bigint().unwrap();

let mut t = 60.to_bigint().unwrap();

let mut i = 2.to_bigint().unwrap();

let mut res: Vec<i32> = Vec::new();

for _ in 0..limit {

let digit: BigInt = ((&i * 27 - 12) * &q + &r * 5) / (&t * 5);

res.push(digit.to_i32().unwrap());

let mut u: BigInt = &i * 3;

u = (&u + 1) * 3 * (&u + 2);

r = &u * 10 * (&q * (&i * 5 - 2) + r - &t * digit);

q *= 10 * &i * (&i * 2 - 1);

i = i + 1;

t *= u;

}

res

}

What is important to notice here is that we return a promise to Javascript. In the Rust code, we create a new runtime for handling asynchronous function executions from which we build a promise that gets returned to JavaScript.

Moving on, we have to create the AWS Lambda function targeting the NodeJS Lambda Runtime. The simplest way to do this is to create a NodeJS project using npm init with app.js file as the entry point and install the Rust dependency as mentioned above.

In the app.js we can build the Lambda handler as follows:

// Import the dynamic library using commonjs

const compute_pi = require("compute-pi-rs");

// Build and async handler for the Lambda function. We use await for unpacking the promise provided by the embedded library

exports.handler = async (event) => {

const digits = await compute_pi.generate(event.digits);

return {

digits: event.digits,

pi: digits.join('')

};

};

This is it. To deploy this function into AWS, we have to pack the app.js file and the node_modules folder into a zip archive and upload it to AWS Lambda. Assuming our target architecture for the Lambda and for the dependencies match (we can not have an x86-64 native dependency running on a Lambda function set to use arm64), our function should work as expected....or maybe not.

GLIBC_2.28 not found

With our Neon project, we build a dynamic library. One of the differences between dynamic and static libraries is that dynamic libraries can have shared dependencies that are expected to be present on the host machine at the time of execution. In contrast, a static library may contain everything required in order to be able to be used as-is. If we build our dynamic library developed in Rust, we may encounter the following issue during its first execution:

/lib64/libc.so.6: version `GLIBC_2.28' not found (required by .../compute-pi-rs-lib/index.node)

The reason behind this issue, as explained in this blog post, is that Rust dynamically links to the C standard library, more specifically the GLIBC implementation. This should not be a problem, since GLIBC should be present on essentially every Unix system, however, this becomes a challenge in case the version of the GLIBC used at build time is different compared to the version present on the system executing the binary. If we are using cross for building our library, the GLIBC version of the Docker container used by cross may be different than the one present in the Lambda Runtime on AWS.

The solution would be to build the library on a system that has the same GLIBC version. The most reliable solution I found is to use an Amazon Linux Docker image as the build image instead of using the default cross image. cross can be configured to use a custom image for compilation and building. What we have to do is to provide a Dockerfile with Amazon Linux 2 as its base image and provide additional configuration to be able to build Rust code. The Dockerfile could look like this:

FROM public.ecr.aws/amazonlinux/amazonlinux:2.0.20220912.1

ENV RUSTUP_HOME=/usr/local/rustup \

CARGO_HOME=/usr/local/cargo \

PATH=/usr/local/cargo/bin:$PATH \

RUST_VERSION=1.63.0

RUN yum install -y gcc gcc-c++ openssl-devel; \

curl https://sh.rustup.rs -sSf | sh -s -- --no-modify-path --profile minimal --default-toolchain $RUST_VERSION -y; \

chmod -R a+w $RUSTUP_HOME $CARGO_HOME; \

rustup --version; \

cargo --version; \

rustc --version;

WORKDIR /target

In the second step, we will have to create a toml file named Cross.toml in the root folder of our project. In the content of this file we have to specify a path to the Dockerfile above, for example:

[target.x86_64-unknown-linux-gnu]

dockerfile = "./Dockerfile-x86-64"

This toml file will be used automatically at each build. Instead of the base cross Docker image, the specified dockerfile will be used for the custom image definition.

The reason for using Amazon Linux 2 is that the Lambda Runtime itself is based on that. We can find more information about runtimes and dependencies in the AWS documentation about runtimes.

Performance and Benchmarks<<

Setup for Benchmarking

For my previous article Running Serverless Lambdas with Rust on AWS we used an unbounded spigot algorithm to compute the first N digits of PI. We will use the same algorithm for the upcoming benchmarks as well. We had seen the implementation of this algorithm above. To summarize, our Lambda function written in NodeJS will use FFI to call a function written in Rust which will return a list with the first N number of PI.

To be able to compare our measurements with the results gathered for a Lambda written entirely in Rust, we will use the same AWS Lambda configurations. These are 128 MB of RAM memory allocated, and the Lambda being deployed in us-east-1. Measurements will be performed for both x86-64 and arm64 architectures.

Cold Start/Warm Start

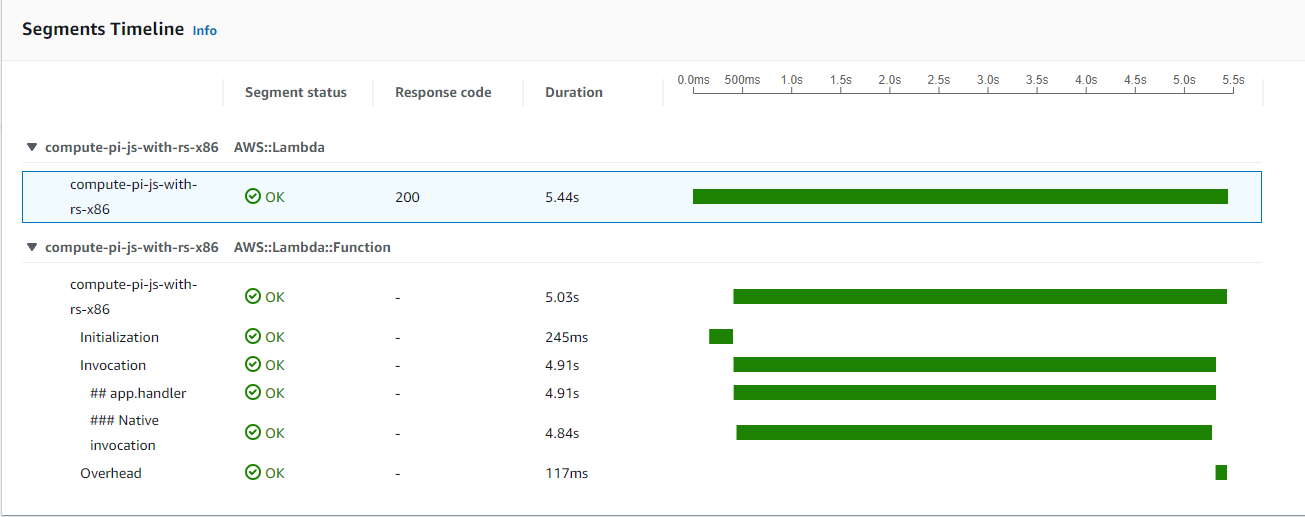

Using XRay, we can get an interesting breakdown of how our Lambda performs and where the time is spent during each run. For example, here we can see a trace for a cold start execution for an x86-64 Lambda:

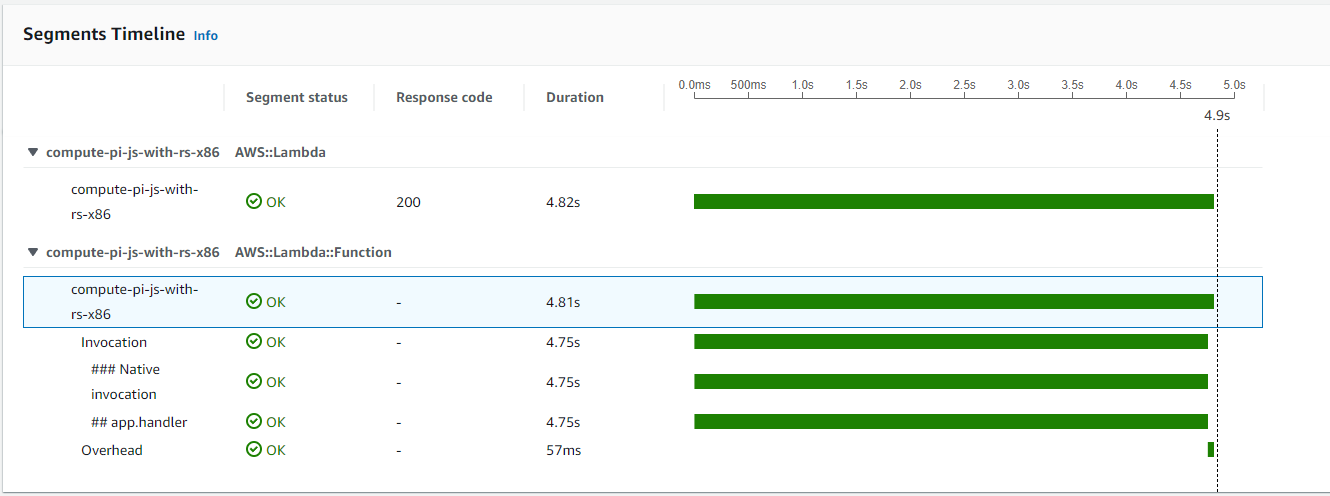

In the following we can see the trace for a warm start in case of the same Lambda:

The initialization (cold start) period is pretty standard for a NodeJS runtime. In my previous article, we could measure cold starts between 100ms and 300ms for NodeJS. The cold start period for this current execution falls directly into this interval.

Performance Comparisons

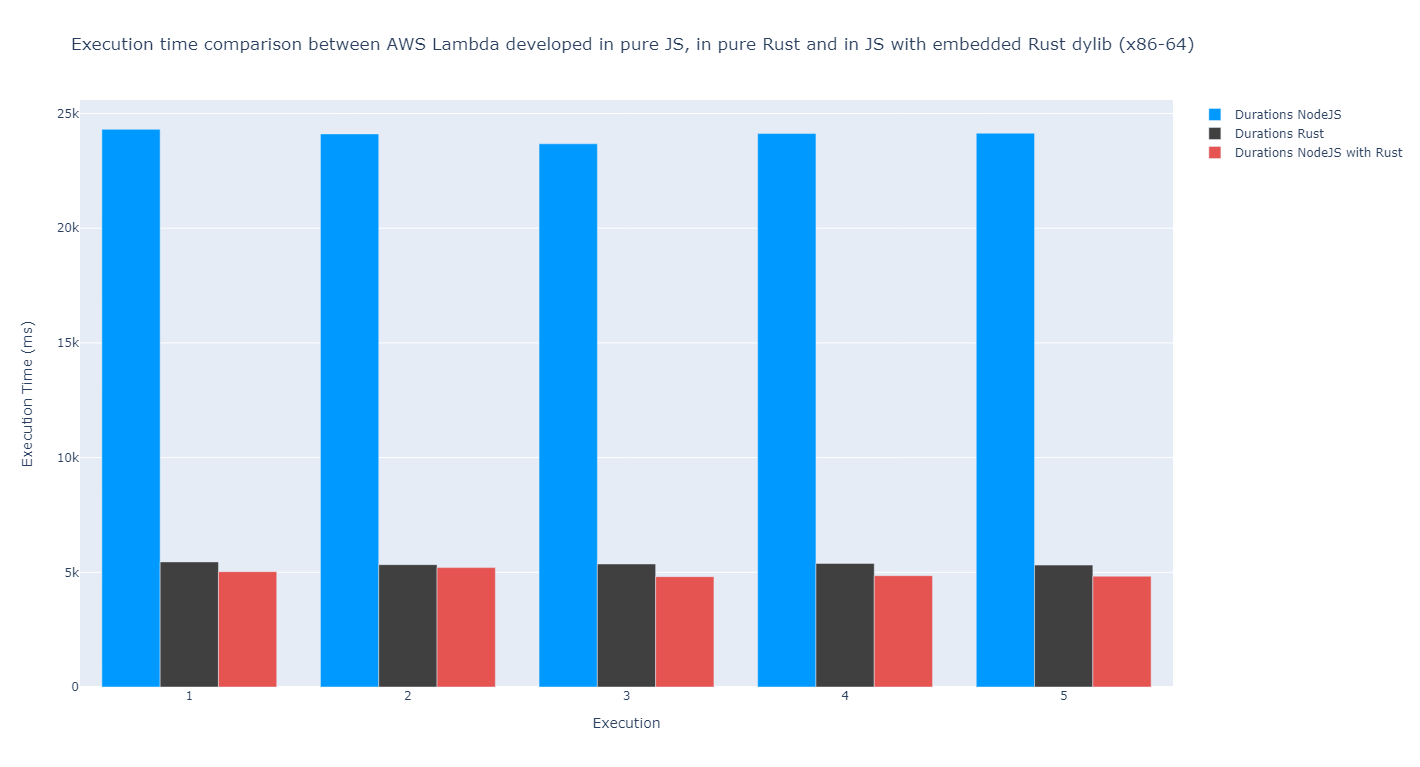

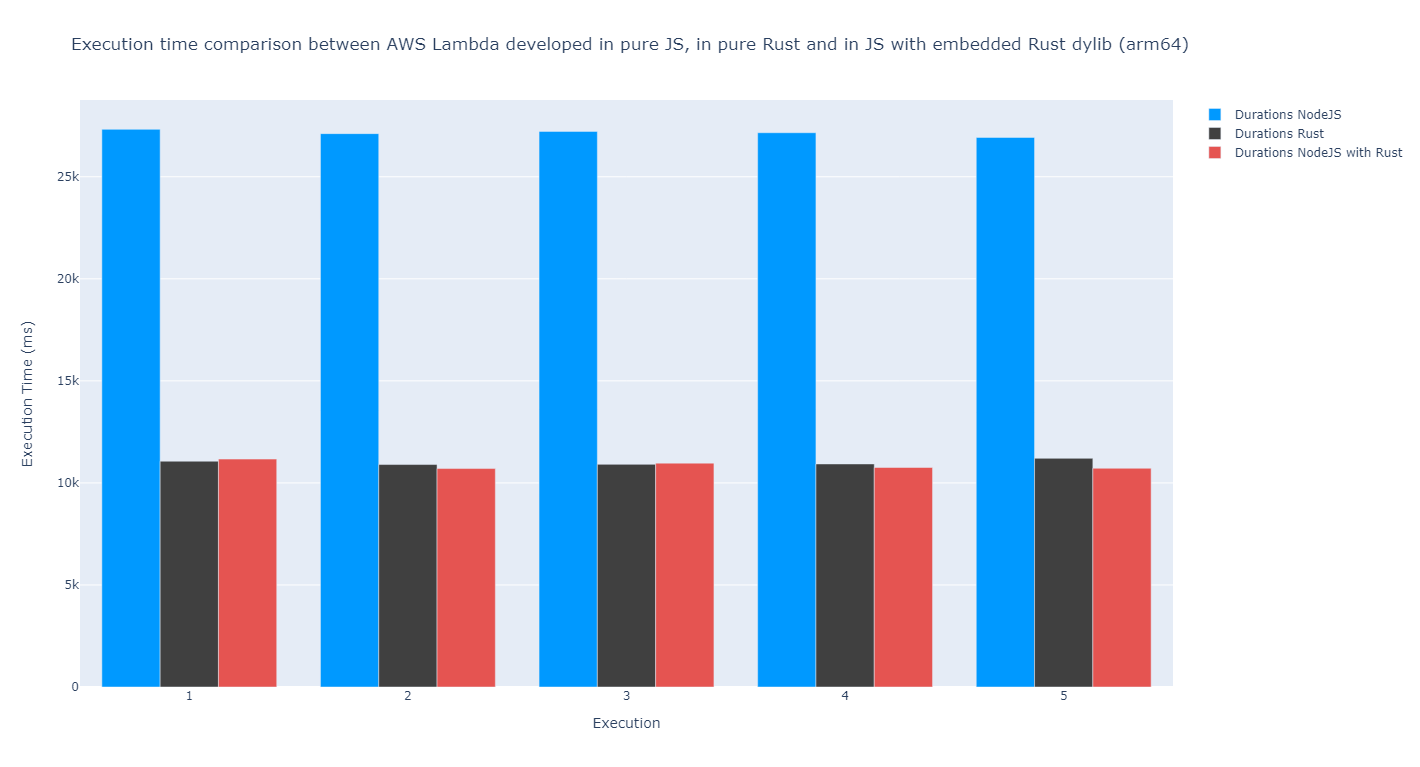

As usual, I measured the running time of 5 consecutive executions of the same Lambda function. I did this for both x86-64 and arm64 architectures. These are the results I witnessed:

| Duration - run 1 | Duration - run 2 | Duration - run 3 | Duration - run 4 | Duration - run 5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| x86-64 | 5029.48 ms | 5204.80 ms | 4811.30 ms | 4852.36 ms | 4829.74 ms |

| arm64 | 11064.26 ms | 10703.61 ms | 10968.51 ms | 10755.36 ms | 10716.85 ms |

Comparing them to vanilla NodeJS and vanilla Rust implementations, we get the following chart for x86-64:

With Graviton (arm64) it looks similar:

According to my measurements, the function with the dynamic library has a similar execution time compared to the one developed in vanilla Rust. In fact, it appears that might be a little bit faster. This is kind of unexpected since there is some overhead when using FFI. Although this performance increase might be considered a margin of error, we should also regard the fact that the measurements were not done on the same day. The underlying hardware might have been performed slightly better. Or simply I was just lucky and got an environment that does not encounter as much load from other AWS users, who knows…

Final Thoughts<<

Combining native code with NodeJS can be a fun afternoon project, but would this make sense in a production environment?

In most cases probably not.

The reason why I’m saying this is that modern NodeJS interpreters are blazingly fast. They can perform at the level required for most of the use cases for which a Lambda function would be adequate. Having to deal with the baggage of complexity introduced by a dynamic library written in Rust may not be the perfect solution. Moreover, in most cases, Lambda functions are small enough that it would be wiser to migrate them entirely to a more performant runtime, rather than having to extract a certain part of it into a library. Before deciding to partially or entirely rewrite a function, I recommend doing some actual measurements and performance tests. XRay can help a lot to trace and diagnose bottlenecks in our code.

On the other hand, in certain situations, it might be useful to have a native binding as a dynamic library. For example:

- in the case of cryptographic functions, like hashing, encryption/decryption, temper verification, etc. These can be CPU-intensive tasks, so it may be a good idea to use a native approach for these;

- if we are trying to do image processing, AI, data engineering, or having to do complex transformations on a huge amount of data;

- if we need to provide a single library (developed in Rust) company-wise without the need for rewriting it for every other used stack. We could wrappers, such as Neon, to expose them to other APIs, such as the one of NodeJS.

Links and References<<

- Foreign function interface: Wikipedia page

- NodeJS - C++ addons: NodeJS docs

- GitHub - node-ffi: GitHub

- Neon: https://neon-bindings.com/docs/introduction

- Node-API (N-API): NodeJS docs

- Tokio Runtimes: docs.rs

- Building Rust binaries in CI that work with older GLIBC: kobzol.github.io

-

cross- Custom Docker images: GitHub - Lambda runtimes: AWS docs

- Running Serverless Lambdas with Rust on AWS: ervinszilagyi.dev

The code used in this article can be found on GitHub at https://github.com/Ernyoke/aws-lambda-js-with-rust